In my historical novel, ROBBING THE PILLARS, Judge Dandridge bemoans the damage done to California’s reputation by the notorious “Legislature of 1000 drinks.” (… page 55)

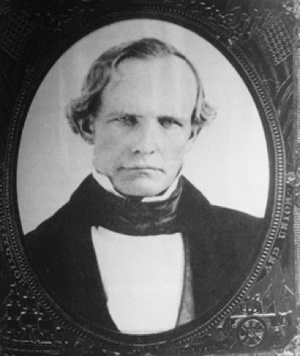

Peter Hardeman Burnett – photo courtesy of California Historical Society

Despite their crudeness, more passion and purity of focus existed in California’s “legislature of a thousand drinks” than the most sophisticated and well-financed groups of legislators that followed. This moniker became indelibly attached to the first state legislature held in a make-shift capital of old San Jose. The high-spirited call to action is attributed to Senator Thomas Jefferson Green who challenged his lawmaking brethren at the close of each day with a cry of, “Let’s have a drink! Let’s have a thousand drinks!” Some say his animated adjournments were meant to cultivate popularity for his future ambitions. Nevertheless, his summon was seldom declined and history records the atmosphere changed little for the second session.

In truth, these men possessed no power or funding with which to become corrupt. Yet, the early days so vilified the first legislature that the people demanded more. Those with an eye for exploiting opportunity came later.

Details of their history reveal an isolated, frontier wilderness – tasked with a herculean feat. After California was ceded to the United States in 1846 following the Mexican War, the area was regulated by a long succession of military governors. Given that the US government deferred bestowing even territorial status while arguing on the balance of slave/non-slave states, Californians struggled with the existing Spanish-Mexican law and alcaldes system. The gold boom escalated their population by staggering proportions, exposing the lack of infrastructure to support the influx of pioneers arriving daily from all over the world. San Francisco’s magnificent harbor was jammed with abandoned vessels whose crews deserted in favor of the gold fields and created an extreme shortage of incoming goods to service an exploding population.

Few gold-hounds desired California as a permanent address and cared little about its political and governmental aspirations. Mining camps opted for self-governing mining codes. Vigilante justice became the cornerstone of the informal legal system. Lack of brick and mortar jails necessitated arrest, trial, sentence and punishment to be carried out on the same day. Yet, growing numbers of professionals, merchants and farmers needed stability and the reputable civic order of American laws.

Without financial resources to govern and no standing central government, Californians waited expectantly as debates raged in Congress over future statehood. South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun angrily decried their efforts as “impatient and anarchistic”. But in August of 1849, having been passed over by Congress once again, the ignored Californians took matters into their own hands and elected 48 delegates. Refusing to be denied any longer, they sent representatives to meet with the purpose of setting up a provisional government.

In September and October of 1849, the delegates convened in Colton Hall in Monterey to draft a constitution, based largely on the constitutions of New York and Iowa. During this time, they designed a State Seal, created three branches of government as well as their own electoral districts for Assembly and State Senate. As an aside, both Utah and New Mexico also held constitutional conventions in 1849 and both failed. Decades passed before either would reach statehood. California pushed through with their unauthorized constitutional convention, and in the meantime, behaved and operated as a state. As soon as they ratified their constitution on November 13,1849, they immediately put it into motion and elected Peter Hardeman Burnett as their first governor.

The first legislature convened on December 15, 1849 in the capital at that time of San Jose. Burnett took the oath of office December 20, 1849 and that afternoon, led a joint session. By the end of January 1850, the infrastructure of California’s government was in place, though still not recognized. As vilified as they were by the early press, the first legislature ranks as one of the most competent and creative; achieving in just a few months the passage of nineteen joint resolutions and one hundred and forty-six acts. Not until the “Compromise of 1850” was reached did they attain official statehood on September 9, 1850. The second legislature, also held in San Jose, set out to portray a more disciplined public image.

Reasons for the disdain of the press were varied. The call for “a thousand drinks”, was born largely of boredom, as there was little sophistication or entertainment. The bars, saloons and gambling dens thrived as the only diversions in town. Most of the reporters hailed from San Francisco and voiced opinions that the area of San Jose and its legislators to be “crude” and “lacking in refinement.” To the observer, it was the true informality of the proceedings that suggested a deficiency of serious commitment. Accounts stated, that during debates, elected officials engaged in smoking, whittling, and fiddling with guns. The press openly targeted the sessions, finding fault with the results.

In addition to the undignified manner of their proceedings, California’s rampant flood problems kept lawmakers on the move, also earning them the nickname “legislature on wheels” as the capital shifted from San Jose, to San Vallejo, before settling in Sacramento, and even then convening for a brief stint in San Francisco, when flood waters sent them scurrying to higher ground.

To their credit, these first legislators were forward thinking for their time, encountering situations uniquely Californian. They settled on more progressive solutions in the case of property rights for women – allowing women to retain sole rights to all property obtained before and during marriage, as previously dictated by Spanish law. They also voted down the governor’s petition to regulate the immigration of free blacks into California.

In fact, it would appear that subsequent legislatures suffered greater issues of blunders and corruption due to the growth of extreme partisanship in burgeoning political parties. (As they say, hum me a few bars of that tune, I think I know it.) Legislators began focusing on their role in electing state senators; to the point of beginning a system of kickbacks, appointments of federal contracts, and an increase of lobbyists following the advance of special interests such as banks, railroads, mining tycoons, captains of industry and agriculture.

Governor Burnett resigned shortly after the second legislature convened, stating a need to return to his suffering business. During his tenure, he was more concerned with costs and rules for running the government, and less decisive in areas of social issues of the day or loftier goals for growth of the state. A man of reserved and reflective nature, it was said he never adapted to public life and criticism. Lieutenant governor, John McDougal was elevated as California’s second governor. In a sharp detour in demeanor, McDougal’s jovial, unrefined persona was at first embraced. His personal habits of drinking, gaming, and subsequent petty squabbles with fellow legislators increased until eroding his reputation completely. He became ridiculed as, “the gentleman drunk,” again stoking recollections of those famous “thousand drink” legislators. Given the trivial matter of his disputes, McDougal’s fatal political mistake came when he battled with the San Francisco vigilantes, with no power to enforce his proclamations to prevent their right to act. Once the only law to stand between a law-abiding citizen and total chaos, the vigilantes were decisively well entrenched in authority and popularity.

The destiny of some members, creates an interesting testament to the wild and fluid times of the original “legislature of a thousand drinks”. From their midst, both sides of the Civil War were represented. Two members voted for laws banning duels, yet died in such contests of honor. Two delegates were later declared insane, one committed suicide, and yet another was murdered by the widow of a fellow legislator.